Kakiseni.com

Kakiseni.com, 12 July 2006.

Take The Lead

Choreography for non-choreographers: The dance of democracy

by Kathy Rowland

Can I use the word “inscrutable” to describe an ethnic Chinese man without being accused of resorting to cliché? Because inscrutable is really the adjective that springs to mind when I think of James Lee, the chess master, moving bodies like pawns in Myra Mahyuddin's A Sleepwalker in Transit, on a rainy Sunday afternoon outside Central Market.

Not stoic, not impassive, and God forbid, not neutral. Inscrutable.

See, the problem sometime with trying to avoid the pitfalls of cliché is that it can deprive you of the most appropriate, concise way of describing something.

I felt that as I watched the performance that resulted from the Choreography for Non-Choreographers workshop, helmed by Marion D’Cruz of Five Arts Centre. Organised as part of a year-long series of workshops under the ‘Krishen Jit Experimental Workshop Series 2006’, CNCW saw 11 individuals, none of whom had any formal dance training, work with choreographer Marion D’Cruz over six weeks towards a public performance in a site specific space.

The CNCW clearly follows on the success of Marion’s earlier work using non-dancers in dance. Such wilful disregard for genre is of course, not new. Having first surfaced in the hothouse of the 60s, it has in fact suffered the fate of all innovation – institutionalisation. It nonetheless remains a useful means of freeing dance from the confines of bodies schooled in a particular movement vocabulary. If I can use a sports analogy, imagine teaching Thierry Henry to dive. How does the agility, speed, and stamina required of a field sport transform itself into the singular moment of control and release in diving? If you can get past imagining Thierry in Speedos, you’ll see what Marion, in another context, was getting at.

CNCW is framed within this trajectory – a democratisation of the process of choreography. It can be argued that choreography is perhaps less codified in its publicly accepted meaning than dance is. The term itself, while originally used to describe dance notation, is, today, easily applied to any deliberate act of creating a situation, movement, and action. Presumably, this makes it more readily entered upon by those not formally trained in it.

Furthermore, if you accept that all movement is thought, then it can be argued that choreography is the deliberate objectification of that thought, into a process of creating movements whose ultimate aim is to draw attention back to the thought that determines the movement.

With all of this spinning in my head, I arrived to James Lee’s “Will you Please Be Quite Please?”, the first of 11 pieces, all strung together by Marion to form a 55-minute non-stop performance. With its dependence on verbal rather than physical movement, it was an interesting choice to open the show with. Phrased as request-demand-implore-retreat, the piece was marked by an apparent randomness of movement that in fact is structurally designed to lead June and Gabrielle into direct confrontation with each other. The group then forms a cocoon into which the plaintive voice of dissent “I will not be quite please” voiced by Gabrielle, retreats, thereby immediately relegating her counter stance as an act of capitulation rather than defiance. It was an in-your-face beginning that unfortunately, fizzled out into a nothingness almost immediately. Opening gimmick rather than opening piece perhaps best describes it.

The next piece, Gabrielle Low’s “24 minutes in Kuala Lumpur, 64 minutes in Jakarta” explored the variances of income and spending power between the two cities. While perhaps predictable in its use of the ubiquitous icon of American imperialism, the Big Mac, the piece was conceptually sound, and successfully distilled the statistics of inequality and CPI into a delightful depiction of gluttony. June Tan’s “Cita-Cita Saya”, was of a piece with Gabrielle’s in its look at the creation of collective consumer desire. Both pieces also neatly reconfigured everyday movement into the performative through repetition and exaggeration, which – and this is important I think – spoke in a humorous and direct manner to the Central Market crowd.

Vernon Adrian Emuang’s “Unrequited” takes as its departure point the dilemma of the non-bumiputra Malaysian. Structured as a slow moving ensemble of layered bodies shadowing a leader, the work evoked a strong sense of ritual which develops into a kind of collective miasma. While it perhaps adequately comments on our willingness to subjugate ourselves in the hopes of gaining acceptance, it failed to fully develop the twin emotions of desire and rejection that is at the heart of this relationship between non-bumiputra citizen and state. I have to say that the opening gesture of the daulat made me physically cringe – talk about a cliché that can be done without.

The conundrum of course is that as boundaries of genre and form become more and more blurred, the old markers of ‘dance’, ‘physical theatre’, ‘theatre’ becomes increasingly unreliable. One is generally reluctant to say that something is this or that, or is not this or that, for fear of being exposed as hopelessly conventional.

As I watched the performance though, that word ‘dance’, like ‘inscrutable’, kept insinuating itself to me.

Many of the works, or particular movements within pieces, drew a direct line back to the conventions of both traditional and modern dance – the hold and release, the lifts and rolls, the cluster and scatter.

It appeared that rather than utilise their non-choreographic sensibility within the realm of choreography, the participants choose instead to work within the safety net of their newly acquired knowledge of dance movements. Too few of them broke free from the accepted idea of choreography and its relationship to existing images/movements of dance. It seemed like a missed opportunity to use their outsider status to energise the act of choreography, and dance.

“Damaged” by Adrian Kisai for example seemed like a primer on contemporary dance movements – from stupor to frenzy, from contortions to cartwheels, from loose pairings to strict oppositional structures – but begged the question: to what purpose?

Likewise, Hari’s “Don’t Wake Me Up, I’m Sleeping”. While it transitioned beautifully from the preceding piece by Kim (“The More We Get Together”) like an unfolding flower of bodies, it then committed the unforgivable sin, in my mind at least, of using silat movements in its lament of the lack of personal courage in the face of great evil. Perhaps there was a time when such use was revolutionary, relevant, necessary, etc. Today, it is the dance equivalent of “muddy bunga”, to quote a recent attempt at musical theatre.

I was also disappointed that despite the much-bandied about 'site specific' claim, none of the works actually engaged with the dynamics of the public space in a meaningful way. In fact, almost all the works were confined to the square dance lino set on the pavement.

A further complication, a fundamental one at that, was the fact that the pieces were performed by the participants of the workshops themselves.

Predictably, Mark, who is the most experienced performer of the lot, was the most watchable. The dynamics of performance in improvised spaces also seem to fit his demeanour particularly well. He has an angular rigor mortis frenzy (you have to see it to comprehend the oxymoron), which was put to good use in Hari’s, Gabrielle and Pang’s pieces. June Tan may be a performance virgin, but she has the kind of chutzpah that makes her a natural on stage. She turned in a highly sympathetic performance in the opening piece, and again in Gabrielle’s and Pang Khee Teik’s works. The revelation for me however was Myra Mahyuddin. She has a certain self-contained power on stage that makes you watch her carefully, desiring both the secret of her calm, as much as a glimpse of the inner turmoil that, surely, surely must lie beneath. Or so her stage presence makes you believe.

James Lee was, as I mentioned earlier, particularly effective in Myra’s piece, while Gabrielle Low also was noteworthy for her ability to appear detached, which invokes a particular kind of danger – of the unpredictable perhaps – when she works it. Adrian Kisai conveys a committedness in performance, but I did feel that this is perhaps not the best medium for him. He may be body beautiful, but he’s certainly not body comfortable on this stage. It would be interesting to see him in more character driven work in the future.

Which leads me to question the framing of the workshop. Was this a choreography for non-choreographer cum dance for non-dancers workshop? Because as an audience, we were cued to deal with the intentional distancing between form and skills presented by the workshop, but there was literally no discourse about the imposition of non-dancers into the mix. One therefore was dealing with the lack of skills on a performative level, which distracted from any real engagement with the choreographic intent of the work. It’s tempting to speculate the outcome of supplying these same choreographers with formally trained performers. What violence upon the sacred realm of movement would that have served up?

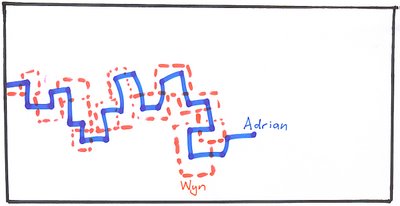

The pieces which worked best were those which dealt with these limitations. Pang Khee Teik’s Hallelujah peopled the dance floor with couples enacting minitue dramas of desire and decline in the guise of slow dancing. I felt that it was the first piece to bring a level of discomfort to the audience. Myra and Kim’s caressing embrace, a whisper away from fulfillment juxtaposed beautifully against the struggle for disengagement that seemed to be at the root of Mark and Vernon’s wrestling. Gabrielle Low, immobilised upon Adrian Kisai’s back seemed to speak volumes in the blankness of her stare, while the act of reaching out and deflection between James Lee and Wyn formed a beautiful ballet of hands, where feet obviously had little rhythm.

Mark Teh’s piece took the idea of choreographer to its more abstract sense – choreography of nationhood via the state’s largest organ, the mass media. Two performers, Myra and Gabrielle, write the day’s headlines with chalk on the ground. With all the frenzy of moving body parts it’s not immediately obvious that the words form an ever enclosing grid which actually shrinks the movable space. Through a series of determining moves, the performers are corralled into a corner, like sheep. There, a formation that replicates the spectacle of the national day parade takes shape. Faster than you can sing “Mamula Moon”, the performers whip out plastic flags, and begin to wave them. Then they eat them. Talk about being force-fed a cheap, plastic form of nationalism.

The accidental audience at Central Market seem enthralled by the entire performance, and frankly, so was I. Despite my very many problems with the performance, it was an afternoon of art with risks, and risk takers are what we desperately need today.

So, dance or not dance? Is that even a question worth asking? Because, stepping away from the individual pieces, is it not possible to view the entire project-workshop and performance as one tightly choreographed event? The choreographer, in the guise of the facilitator, organises a series of encounters with 11 individuals, which turns them into the building blocks, each unit not merely moving, as would a dancer, but first conceptualising, then creating, then enacting each movement – which she then constructs into a full performance?

And does not this act of meta-choreography illustrate perfectly that choreography is manipulation ¬of limbs, of stances, of desires, of thought, of actions, of citizens, of nations?

Should we not be asking ourselves if we have just witnessed Marion D’Cruz’s most recent, most audacious and most accomplished choreography to date?

~ ~ ~

Kathy Rowland is co-director of Kakiseni.